The U.S. Department of Agriculture reported last week that a pig at a backyard farm in Oregon was infected with bird flu.

As the bird flu situation has evolved, we have learned that the A/H5N1 strain of the virus is infecting a range of animals, including a variety of birds, wildlife and dairy cattle.

Fortunately, we have not seen sustained spread between people at this stage. But the detection of the virus in a pig marks a worrying development in the trajectory of this virus.

How did we get here?

The most worrying type of bird flu currently circulating is clade 2.3.4.4b of A/H5N1, a strain of influenza A.

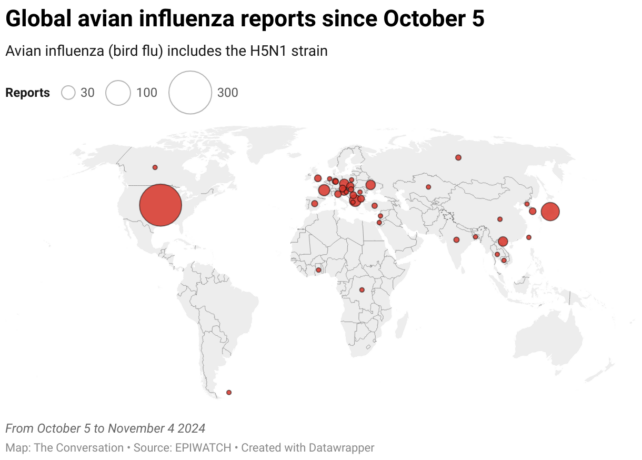

Since 2020, A/H5N1 2.3.4.4b has spread to a large number of birds, wild animals and farm animals that have never been infected with bird flu before.

While Europe is a hotspot for A/H5N1, attention is currently focused on the US. Dairy cattle were first infected in 2024, affecting more than 400 herds in at least 14 US states.

Bird flu has a huge impact on agriculture and commercial food production, as infected poultry flocks must be culled and infected cows can result in contaminated dairy products. That said, pasteurization should make milk drinkable.

While farmers have suffered major losses due to the H5N1 bird flu, bird flu also has the potential to mutate and cause a human pandemic.

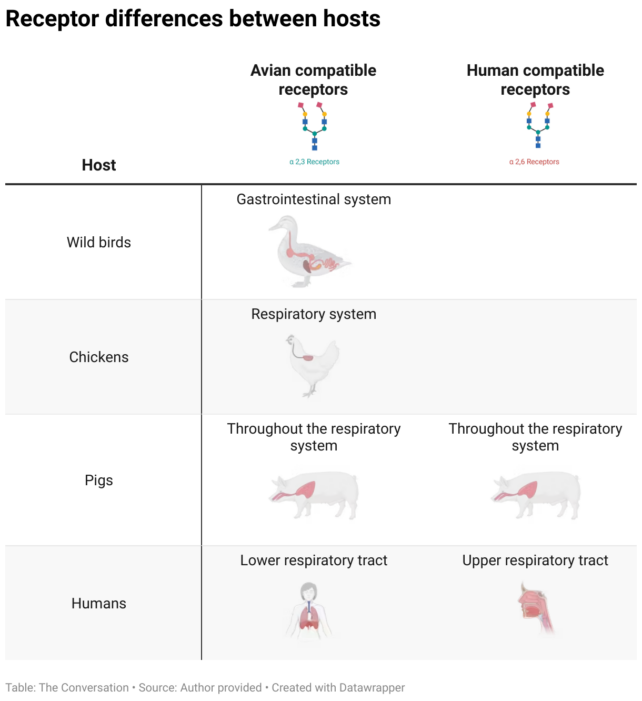

Birds and humans have different types of receptors in their respiratory tract to which flu viruses attach, such as a lock (receptors) and a key (virus). The attachment of the virus allows it to enter a cell and the body and cause disease. Avian flu viruses are adapted to birds and spread easily among birds, but not among humans.

To date, human cases have mainly occurred in people who have been in close contact with infected farm animals or birds. In the US, most were farm workers.

The concern is that the virus will mutate and adapt to humans. One of the key steps to achieve this would be a shift in the affinity of the virus from the bird receptors to those in the human respiratory tract. In other words, if the virus’s ‘key’ were to mutate to better match the human ‘lock’.

A recent study of a sample of A/H5N1 2.3.4.4b from an infected human yielded concerning findings, identifying mutations in the virus with the potential to increase transmission between human hosts.

Why are pigs a problem?

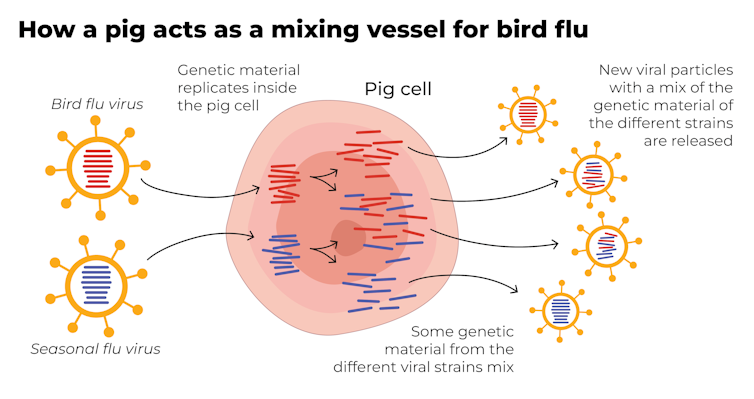

A human pandemic flu variant can arise in different ways. One of these involves close contact between humans and animals infected with their own specific flu viruses, creating opportunities for genetic mixing between avian and human viruses.

Pigs are the ideal genetic mixing vessel to generate a human pandemic influenza strain because they have receptors in their respiratory tract that both avian and human influenza viruses can bind to.

This means that pigs can be infected with an avian flu virus and a human flu virus at the same time. These viruses can exchange genetic material, mutate and become easily transmissible to humans.

(The conversationCC BY-SA)

Interestingly, pigs were less susceptible to A/H5N1 viruses in the past. However, the virus has recently mutated to infect pigs more easily.

In the recent case in Oregon, A/H5N1 was detected in a pig on a non-commercial farm after an outbreak occurred among poultry housed on the same farm. This A/H5N1 strain came from wild birds, and not from the strain that is widespread in American dairy cows.

The infection of a pig is a warning sign. If the virus enters commercial piggeries, the risk of a pandemic would be much greater, especially as the U.S. enters winter and human seasonal flu begins to increase.

How can we limit the risk?

Surveillance is key to the early detection of a potential pandemic. This includes extensive testing and reporting of infections in birds and animals, as well as financial compensation and support measures for farmers to encourage timely reporting.

Strengthening global influenza surveillance is critical because unusual spikes in pneumonia and severe respiratory illnesses could signal a human pandemic. Our EPIWATCH system looks for early warnings of such activity, which can accelerate vaccine development.

If a cluster of human cases occurs and influenza A is detected, further testing (called subtyping) is essential to determine whether it is a seasonal variant, an avian species resulting from a spillover event, or a new pandemic variant.

Early identification can prevent a pandemic. Any delay in identifying an emerging pandemic strain allows the virus to spread widely across international borders.

Australia’s first human case of A/H5N1 occurred in a child who contracted the infection while traveling in India and was hospitalized with illness in March 2024. At the time, testing showed influenza A was present (which could be seasonal flu or bird flu), but subtyping to identify A/H5N1 was postponed.

This type of delay can be costly in the event of a human-transmissible A/H5N1 event that is believed to be seasonal flu because the test is positive for influenza A. Only about 5% of tests that are positive for influenza A are continued divided into Australia and most countries. .

In light of the current situation, there should be a low threshold for subtyping influenza A strains in humans. Rapid tests that can distinguish between seasonal flu and H5 flu A are emerging and should be part of governments’ pandemic preparations.

A greater risk than ever before

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says the current risk from H5N1 to the general public remains low.

But now that H5N1 can infect pigs and show mutations of concern for human adaptation, the level of risk has increased. Because the virus is so widespread among animals and birds, the statistical probability of a pandemic occurring is higher than ever before.

The good news is that we are better prepared for a flu pandemic than other pandemics because vaccines can be made in the same way as seasonal flu vaccines. Once the genome of a pandemic influenza virus is known, vaccines can be adapted accordingly.

Partially adapted vaccines are already available, and some countries, such as Finland, are vaccinating high-risk agricultural workers.![]()

C Raina MacIntyre, Professor of Global Biosecurity, NHMRC L3 Research Fellow, Lead, Biosafety Program, Kirby Institute, UNSW Sydney and Haley Stone, Research Associate, Biosafety Program, Kirby Institute & CRUISE lab, Computer Science and Engineering, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.