Early Homo sapiens and their Neanderthal cousins began burying their dead around the same time and roughly the same place, some 120,000 years ago. This suggests that the two species had, at least partially, a shared culture at the time.

A new study of these ancient burial sites in the Levant region of western Asia reveals other similarities and differences in the way these two closely related groups of people buried their dead.

Finding some of the sites predates other Neanderthal burials in Europe Homo sapiens burials in Africa, the study suggests that this is where the practice of burying the dead first began.

And according to researchers from Tel Aviv University and Haifa University in Israel, the 17 Neanderthals and 15 Homo sapiens sites show that in addition to some cultural overlap, there may also have been competition.

“We hypothesize that the increasing frequency of burials by these two populations in West Asia is related to the intensified competition for resources and space resulting from the arrival of these populations,” the researchers write in their published paper.

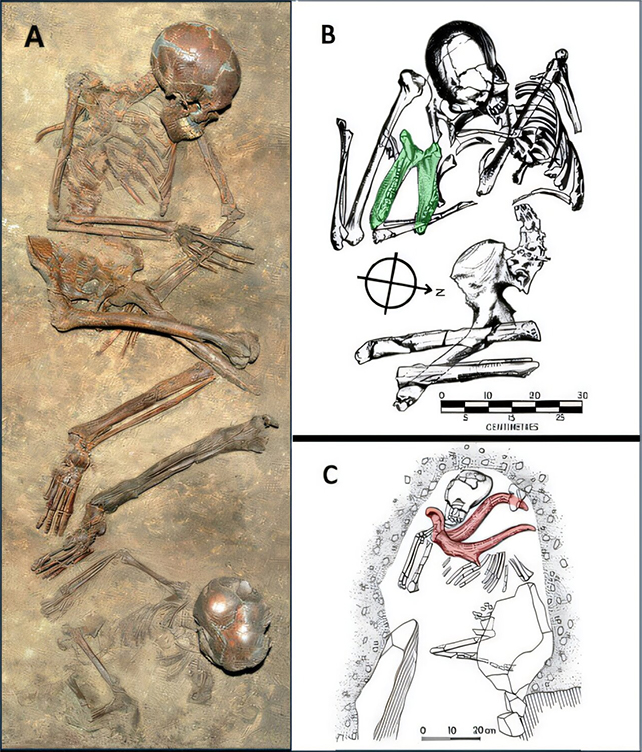

The difference between deliberately buried bodies and bones covered by the elements where they fall is not always clear. The researchers looked for different skeletal positions, grave goods or markers, and evidence from graves to reach their conclusions.

They discovered that both Neanderthals and H. sapiens would bury people of any age, although infant mortality was more common among Neanderthals. Both groups also added a variety of goods to the graves, including small stones, animal bones, or horns.

However, Neanderthals tended to bury their dead deeper in caves H. sapiens were buried in cave entrances or rock shelters. What’s more, H. sapiens skeletons were usually in some sort of fetal position, while Neanderthal skeletons were discovered in one of several arrangements.

The differences don’t end there either. Neanderthal burials increasingly used rocks – perhaps as rudimentary gravestones H. sapiens burials contained more decorative objects, including ocher and shells, which Neanderthals did not use.

“While Neanderthals and Homo sapiens share many aspects of their material culture to the extent that they become indistinguishable from each other, when it comes to burials the picture is more complicated,” the researchers write.

Although there would have been some population pressure during the Middle Paleolithic, with both groups of hominids arriving in the Levant at similar times, the researchers think this only partially explains the sudden introduction of burials.

It’s also worth noting that after Neanderthals went extinct some 50,000 years ago, human burials in this part of the world seemed to cease for tens of thousands of years – another intriguing data point worth exploring further.

“The next outbreak of burials in the Levant occurred at the end of the Paleolithic and accompanied the early sedentary society and the last hunter-gatherers – the Natufians,” the researchers write.

The research was published in The Anthropology.