Glioblastoma is the most common and deadliest form of brain cancer. Patients face a bleak prognosis: the average survival after diagnosis is between 12 and 15 months. And only 6.9% of patients survive longer than five years, making it one of the worst survived cancers.

The toll this cancer takes goes beyond survival. Patients may experience symptoms such as headaches, seizures, cognitive and personality changes, and neurological disorders. These symptoms can drastically affect their quality of life. But despite the urgent need, no targeted treatments exist for this devastating disease.

Researchers now believe that immunotherapy, which uses the immune system to target cancer cells, could be a turning point in the treatment of glioblastoma.

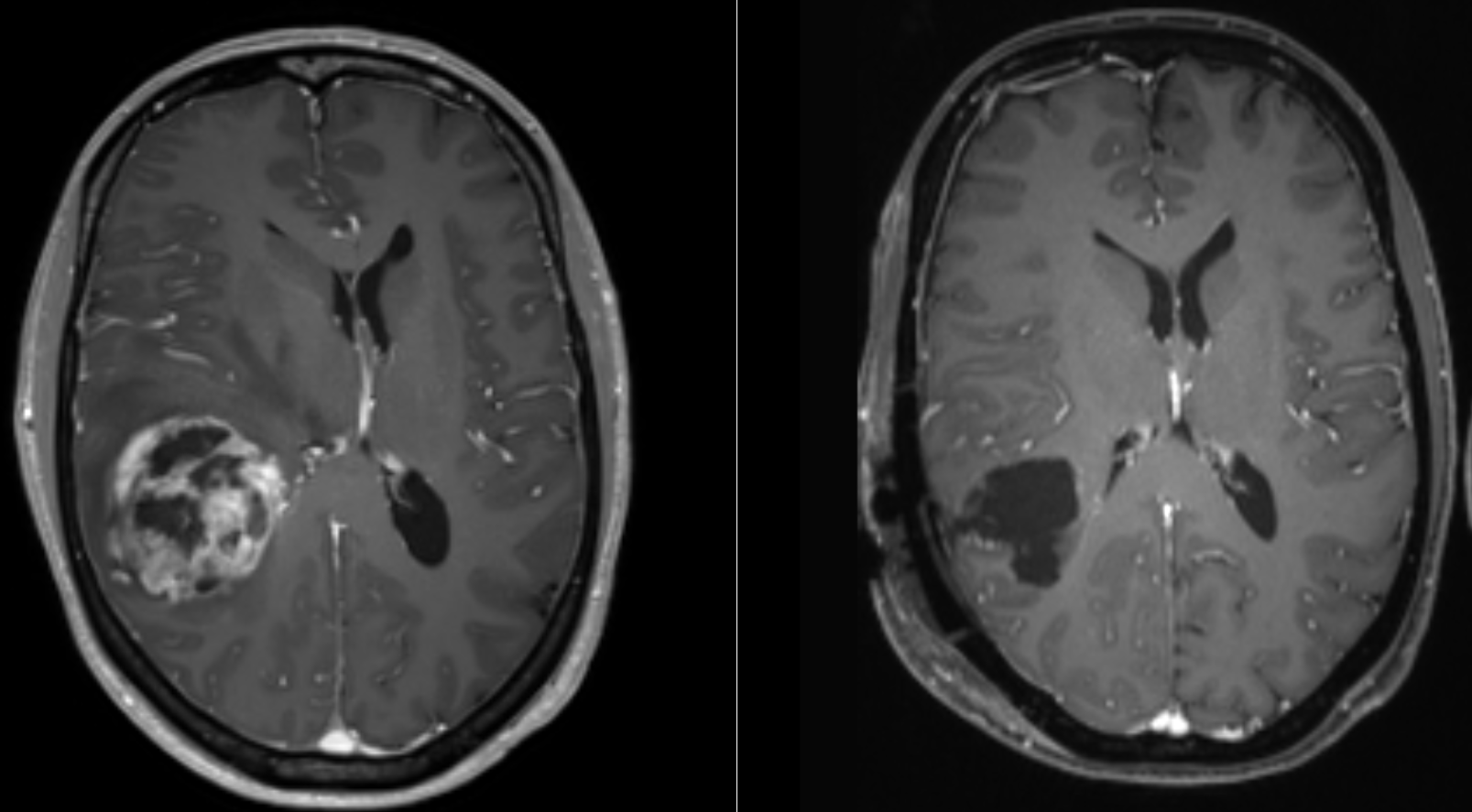

Glioblastoma is a naturally occurring tumor that belongs to a group of brain tumors called ‘gliomas’, which originate and grow in the brain and spinal cord. Glioblastoma, classified as a grade 4 tumor by the World Health Organization, is one of the most aggressive cancers.

In Britain, an estimated 3,200 new cases of glioblastoma are diagnosed each year, making up a significant proportion of the 12,700 total brain and central nervous system tumors reported annually. Globally, there are approximately 3.2 to 4.2 cases per 100,000 people annually. This translates to approximately 150,000 new cases per year worldwide.

Standard treatments for glioblastoma – such as surgery, radiation and chemotherapy – are often only temporarily effective. The tumors are highly resistant to these treatments due to the cancer’s ability to suppress immune responses and the presence of the blood-brain barrier, which prevents most drugs from reaching the brain.

After surgery, the tumor often returns and can spread to other parts of the brain. This leads to new challenges for both patients and doctors.

Immunotherapy

The field of immunotherapy is rapidly evolving, with continued research expanding its potential applications for various diseases. There are currently approved immunotherapy treatments available for several cancers, such as melanoma, breast and lung cancer.

Immunotherapy can also be used to treat autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis, infectious diseases such as HIV and hepatitis B and C, and allergic conditions.

For the treatment of glioblastoma, immunotherapy represents a promising but complex avenue. Due to the highly adaptive nature of the tumor, glioblastoma exhibits different mutations in different parts of the brain. This makes it difficult to target. Still, researchers are optimistic.

Recent studies have shown that immunotherapy can be safely administered via injections into the cerebrospinal fluid. Scientists are now investigating how to adapt these methods to more effectively penetrate the tumor.

Despite the promise of immunotherapy, making it effective for glioblastoma remains a challenge. Funding shortages have hindered brain cancer research in the past. But new initiatives are helping recruit researchers from other fields to tackle glioblastoma. This also applies to researchers like me.

For twenty years I have studied how the immune system can be manipulated and modulated during cancer and chronic infections. More recently, I have been studying how immune cells communicate and disrupt brain function, resulting in the onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

I now apply that knowledge and experience to glioblastoma, where I investigate how to bypass the barriers that prevent the treatment from reaching the tumors. My work is part of a global effort to develop and test immunotherapy treatments specifically for glioblastoma.

While glioblastoma remains a complex and challenging disease to treat, immunotherapy offers a potential path to better outcomes for patients. But to date, there are no approved clinically available immunotherapies to improve the lives of patients with glioblastoma.

It is also important to note that not all cancers respond to immunotherapy. And there may be immune-related side effects, such as organ inflammation. Careful consideration must be given to ensure that any treatment does not result in swelling of the brain.

The method of administration of these medications is also vital. Treating a patient with a simple injection in the arm and into the blood, or via the spinal cord, is better than, for example, surgery on the brain. These considerations are an essential part of research.

However, the prospects for the use of immunotherapy in glioblastoma remain exciting. As interest and investment in the potential of immunotherapy grow, my fellow researchers and I remain hopeful that we may soon discover more effective treatments for this terrible disease.![]()

Mathew Clement, Research Fellow at the School of Medicine, Cardiff University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.